On March 27, 2017, the Supreme Court will hear arguments in TC Heartland v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC. The case concerns venue for patent litigation and has the potential to be one of the most significant procedural cases related to patents of the last twenty years.

By way of background, prior to the late 1800’s, defendants could be sued in federal court wherever they were inhabitants or could be found when the suit was served. Thus, a person traveling by train among districts or states, could be sued at each stop along the way if they could be served there. Congress responded to abuses of this approach in 1887 by creating a venue provision that largely limited suit to places where the defendants were inhabited (now, essentially 28 U.S.C. § 1391). Some courts held that the new statute did not apply to suits for patent infringement. Thus, patent defendants were still being sued wherever they could be served.

In 1897, Congress responded by creating a venue statute specifically for patent infringement cases that limited venue to places where the defendant was incorporated or had both committed acts of infringement and had a regular and established place of business (now, 28.U.S.C. § 1400(b)).

Changes made to the general venue provision led to claims that both venue provisions were supplementary, thereby broadening venue for patent cases and largely rendering the venue provision superfluous. Subsequently, in Stonite Products Co. v. Melvin Lloyd Co. (1942), the Supreme Court rejected that claim stating: “We hold that [the patent specific venue statute] is the exclusive provision controlling venue in patent infringement proceedings.” Thus, the definition of “resident” in the general venue provision was not controlling of “resident” in the patent venue provision.

In 1948, the United States Code was again reorganized and revised to use modern phrasing and, again, it was argued that the general venue provision and the patent specific provision were supplementary. In Fourco Glass Co. v. Transmirra Products Corp. (1957), the Supreme Court held, again, that they were not. The Supreme Court stated: “We hold that 28 U.S.C. § 1400(b) is the sole and exclusive provision controlling venue in patent infringement actions, and that it is not to be supplemented by the provisions of 28 U.S.C. § 1391(c).”

In 1982, Congress created the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and vested that court with exclusive jurisdiction for appeals in patent cases. Thereafter, in 1988, Congress again amended the general venue provision and, again, it was argued that the amendments made the venue provisions supplementary. When the issue reached the Federal Circuit in a case called VE Holding Corp. v. Johnson Gas Appliance Co. (1990), the court held that despite Stonite and Fourco, the general venue provision and the patent specific venue provision were supplementary as a result of the 1988 amendments. Accordingly, patentees could bring suit against defendants any place where the defendants were subject to personal jurisdiction and where alleged acts of infringement occurred. Practically speaking, this resulted in nationwide venue for patent cases.

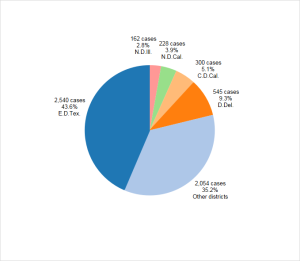

Stripped of the restrictions of the patent specific venue statute, plaintiffs filed suit in those districts they believed were most favorable to them. This led to the rise of the Eastern District of Texas and, to some degree, Delaware as preferred plaintiff venues. Both venues are characterized as having a small number of judges and where litigation itself is a significant factor in the local economy. In the Eastern District of Texas, case assignment procedures mean the plaintiffs can significantly influence which judge is assigned to their case. A few numbers will put the extent of the forum shopping into perspective. Below is a chart showing patent filings by district in 2015.

Further, in 2016, a single judge in the Eastern District of Texas (Judge Rodney Gilstrap) was assigned nearly 25% of all the patent cases filed nationwide (1,119 out of 4,537).

The case that is before the Supreme Court illustrates both the effect of VE Holdings and how venue would be different under the patent specific venue statute. Defendant TC Heartland itself is an LLC organized under the laws of Indiana. TC Heartland has manufacturing operations in Indiana where it makes zero calorie sweetener products. TC Heartland has no operations in Delaware but did drop ship some products (~2% of sales) to Delaware at the direction of an Arkansas customer. All of TC Heartland’s witnesses, etc. are based in Indiana. Plaintiff/patentee Kraft Foods is a Delaware corporation with its principal place of business near Chicago, Illinois. The patent asserted relates to the packing of the sweetener products.

Kraft Foods brought suit in Delaware accusing TC Heartland of infringing the patent by, e.g., selling or using the sweeteners in Delaware as a result of the drop shipments. Relying on VE Holdings, the district court denied TC Heartland’s motion to dismiss or transfer. On a writ of mandamus, the Federal Circuit also relied on VE Holdings and denied TC Heartland’s petition. The Supreme Court granted cert. of TC Heartland’s petition which stated:

The question in this case is thus precisely the same as the issue decided in Fourco:

Whether 28 U.S.C. § 1400(b) is the sole and exclusive provision governing venue in patent infringement actions and is not to be supplemented by 28 U.S.C. § 1391(c).

If the Supreme Court overturns VE Holdings and returns to the view of Fourco, then venue in patent infringement litigations will be guided solely by § 1400(b). Under that view, defendants can only be sued where they “reside” (i.e., their place of incorporation only) or where they have both a regular and established place of business and are alleged to have committed acts of infringement. Under this approach, few cases could be filed properly in the Eastern District of Texas, given its rural nature. However, it is to be expected that retailers (e.g., BestBuy, Walmart, etc.) in the Eastern District of Texas will be used as even more of a pretext for filing suits than they are now. Conversely, many cases may still be filed in Delaware in light of the fact that many potential defendants are incorporated in Delaware. Beyond that, patent litigation should move to the major cities where defendants will have regular and established places of business. As a result, patent litigation will be more evenly spread around the United States and it is to be expected that companies will more carefully consider the advantages and disadvantages of Delaware incorporation.